But there is of course plenty more to do and there is a growing desire among many new and existing owners to explore how we might reduce, or even sever our dependency on fossil fuels. With the ability to harvest power through a combination of solar, wind and hydro generators, taking the next step towards a greener, more sustainable future seems well within our grasp.

We spoke to a number of experts in different aspects of sustainability and yachting. These include electric and hybrid propulsion experts, naval architects, sales and project managers, all of whom are continually exploring new technology and ideas that are driving sustainability and understanding how these can be applied in the yacht world.

Yet, while we can generate power on the move, the rate at which we have become dependent on electrical energy to drive devices from navigational and communication systems, to washing machines and watermakers, it is clear that our appetite for power has grown considerably in recent years. The question now is whether the various green ways of producing it can keep pace.

This is also the gateway to wider debate, that of how we operate our boats and what we expect to be able to achieve. There can be little doubt that more of us are sailing further afield and in many cases for longer. Modern technologies have played a large part in making this possible and now, having experienced a lifestyle that gives us the freedom to roam at will, we need to find better, more efficient ways to keep the show on the road.

Setting power to one side, there are other key issues that come under the sustainability heading, not least the way that we build our boats. For example, is it right to be continuing with glass reinforced plastics or should we be considering alternative materials?

Bio based resins are already making their way into some parts of the construction world, fibres produced from volcanic rock have also demonstrated some impressive structural properties that could rival carbon fibre, while new teak alternatives are providing an interesting route forward with some remarkable new materials.

Some argue that quality blue water cruisers like Oysters are rarely, if ever, scrapped and are therefore a great example of sustainability. With such proven longevity, the need to switch to materials that can be recycled is largely irrelevant.

The reality is that sustainability provides endless avenues of debate with a multitude of factors that can take the discussion off-piste and into the thick of the detail. But the issue of power is currently one of the most popular, in particular how we generate it, store it and use it, as well as considering what role the conventional combustion engine should play.

“I believe there will be areas of the world that will not allow combustion engines to be run in the future,” says electric and hybrid propulsion expert Jamie Marley. “Certain areas will only be accessible by boats with zero emissions. So, at the very least, looking to sustainable solutions now could have a big bearing on where you could go in the future, which could also influence the future value of your yacht.”

Considering what you might want to do in the future is a good starting point, whether you are looking to day sail around the Mediterranean or set off around the world.

Solar power seems like an obvious choice for a yacht and technology is available that can be built-in or retrofitted to your Oyster. However, as Simon Uphill, Lead Electrical Engineer at Oyster Yachts points out, the technology is not up to making a significant contribution to a yacht’s energy needs yet. Add in the cost versus the energy delivered, the return on investment currently makes serious solar power a nice-to-have. As the technology develops, we hope to see strides made in perfecting more efficient and affordable solar solutions.

“Whatever the size of boat, we always begin by talking to the owner in detail about what they are looking to achieve,” explains sales director Richard Gibson. “From here you can start to look at how you will run the boat which, in turn, then leads you to the kind of systems that you might want to consider.

“Then we can discuss some of the key sustainability issues that an owner might have, whether it be generating sufficient power for the hotel services, or electrical power for a hybrid propulsion system. At this level there are some fundamental issues to consider which help focus the mind, such as the ability to motor off a lee shore in 30-40 knots of wind.

“Another is assessing what the main loads for the electrical system will be – is the goal to have silent running overnight, or is a hybrid power train the key objective? Are they looking to charge the batteries using a dedicated hydro generator while on passage, or is the objective to utilise an electrical drive unit that can switch roles to regenerate when the boat is under sail?”

Naturally, these are just starting points and while most would doubtless set their target as using a conventional engine as little as possible, it is worth putting the challenge into context.

“Making a simple comparison between the energy in diesel fuel versus a modern lithium ion battery puts this into perspective,” explains Oyster After Sales expert Eddie Scougall. “A modern lithium battery delivers around 7 per cent of the energy you get from the same weight of diesel fuel. So you need around 14 times the weight in batteries to replace the diesel.”

Naturally, this is simply an illustration of the scale of the issue. In fact it is the technical advantages of lithium ion batteries that are a key factor in enabling the new sustainable approach.

“Although the initial expense is more than for a set of conventional gel batteries, there are some significant advantages,” says project manager Andy Armshaw. “Firstly, the number of cycles the batteries can do in a lifespan is far greater. Ten years ago I managed an Oyster 65 with lithium ion batteries and they were only replaced last year. Compare that to an Oyster 72 I managed with gel batteries and we had to replace these batteries after six years.

“Lithium ion batteries are a lot more usable throughout their range too, in that they can drop to a much lower voltage without any voltage drop in the system. You can charge them more quickly as well, which reduces your generator run time, plus they are much lighter than conventional gels. So, for me they are an easy win.”

But the lithium ion route can provide further knock-on benefits, as lead electrician Simon Uphill explains.

“Mastervolt supply a fuse and isolator kit, which is mounted on a bracket directly on top of the lithium ion batteries. Historically, it has been tricky getting the fuse and isolator in a location close to the batteries, but with this system it’s much easier because the lithium batteries take up far less space than the gel bank, plus you don't need a master shunt because the battery monitoring is built into the batteries themselves.

“Another advantage with a lithium bank is that you can make more efficient use of the fuel that you do use when running your generator. Rather than running a generator partially loaded for some of your equipment, you run your systems off a lithium bank by using an inverter to power these AC loads. You discharge your battery banks over a period of a day and then you run your generator at full capacity for a short period of time to recharge those batteries. The result is that you run your generator far more efficiently.”

But some are looking to go further than this.

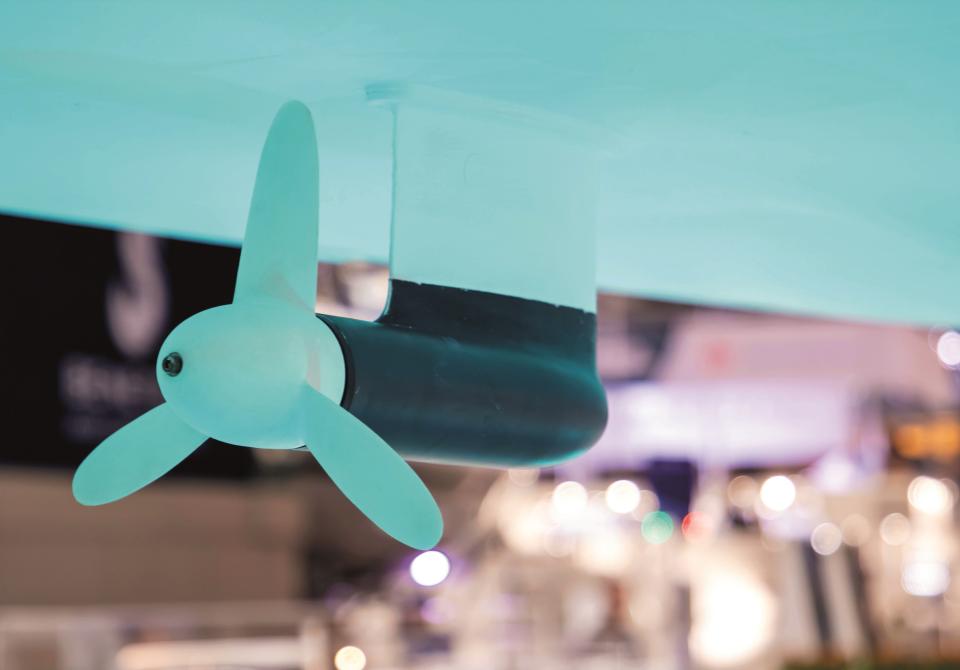

“Parallel hybrid systems put an electric motor between the prop and the propulsion engine,” continues Uphill. “This means that you can power the prop either from the running engine or from the service battery bank if you want to operate silently. The advantage here is that with this system it is possible to use the propellor as a hydro generator. Torqeedo and ServoProp are the two key companies that offer this kind of a system.”

An alternative route for regeneration is the Watt & Sea Pod 600, a dedicated unit that only acts as a hydro generator and not as a propulsion unit.

“The Pod 600 is a small unit with a 280mm propeller that sits just behind the keel, so it's well protected and, given its small size, there is no noticeable drag,” says project manager Andy Armshaw. “We did a load analysis and established that if you’re travelling at 7-8 knots it would generate about 400 amp hours/day. At 10 knots it will increase to around 580 amp hours/day. While this might not cover the complete load, it does mean that the use of the generator could be reduced significantly, especially if you are not running air conditioning.”

But while outputs at this level can be suitable for those who are not running systems such as air-conditioning, designer Tom Humphreys points out where the boundary lies when considering hybrid power systems.

“If your propulsive loads are significantly higher than your hotel loads, it starts to look more favourable to stick with conventional diesel generators,” he says. “But if it’s the other way around, which it could easily be for a blue water cruiser in trade wind sailing, then it starts to look better to go for diesel electric or serial hybrid systems where you are supplying the hotel load more efficiently with variable speed generators. And here, hydrogeneration will do a lot to produce power for hotel loads.”

Oyster has seen good results in this area. They recommend the Watt & Sea Pod 600 — a number of owners are fitting this system to their new Oysters.

But for all the benefits of modern electrical systems and their ability to run green and silent, one of the key concerns for some owners comes down to the practicalities of heading off to remote spots while relying on high tech systems. Given the remote nature of blue water cruising, there is a concern that if repairs are required it could be difficult to find an electrical expert in the same way as you might be able to find a diesel engine engineer.

“Modern systems are extremely clever and go into limp-home-mode well before they break down or the problem becomes a hardware issue,” says Jamie Marley. “I used to be an engineer for Torqeedo and was flying all over the world, but I was travelling to install or commission systems, I wasn’t required to be a flying doctor rectifying problems. It’s easy to underestimate the level to which modern electrical systems can be interrogated remotely and so long as you can get a connection using a mobile phone or a WiFi network, or even a satellite phone, you can usually assess way more than you would be able to diagnose an internal combustion engine.”

So, while technology is changing fast, the options for greener more sustainable cruising are increasing rapidly, while also changing the way that we operate and maintain our boats. And yet, while we start with a natural advantage, the bottom line is that we are barely scratching the surface of what is possible.